Who Were the Scottish Picts? Unraveling Scotland's Most Mysterious Ancient Civilization

by Teresa Finn on May 10, 2025

Table of Content

The Picts were a confederation of Celtic-speaking tribes who lived in eastern and northern Scotland from the Iron Age until the 10th century. Known in Roman writings for their bold body art and remembered today through their carved symbol stones, these Iron Age people left behind a legacy that still shapes Scotland’s identity.

This article explores their world — how they lived, what they believed, the art they created, and how their story became part of the foundations of early Scotland.

1. Who Were the Picts?

The Scottish Picts were an ancient confederation of tribes who inhabited the lands north of the Firth of Forth from around the 3rd century AD until their gradual absorption into the emerging Kingdom of Alba around the 9th century.They are best understood through a few defining characteristics:

A distinct cultural identity: Known for carved symbol stones, unique art styles, and body markings that inspired the Roman name Picti (“painted people”).

A network of tribal kingdoms: Rather than one nation, they formed multiple allied kingdoms — such as Fortriu — linked by shared traditions, language, and political structures.

A resilient, adaptable society: They farmed, traded, built fortified settlements, and resisted Roman expansion, later merging into the early Kingdom of Alba.

Despite their eventual disappearance from written records, the Picts left behind a remarkable legacy in archaeology, place names, and cultural memory — traces that still shape Scotland’s story today.

The Pictish Language

The Picts spoke Pictish, an extinct Brittonic Celtic language related to ancient Welsh and Cornish — not Gaelic. It had its own distinct features and survived until Gaelic became dominant after the Picts merged with Gaelic-speaking Scots in the 9th century.

Evidence of Pictish survives in place names such as aber (Aberdeen) and pit (Pittenweem), as well as in inscriptions and carved stones. By the 11th century, Pictish had largely faded, replaced by early Scottish Gaelic.

The Name “Pict” and Its Origins

The word “Pict” comes from the Latin term Picti, which means “painted people” — a name coined by the Romans who described their body art or Pictish tattoos. While some considered it an insult, the Picts people eventually embraced the name, making it their own during the height of their power.

Myth and Reality of Their Origins

Legends tell of the Picts arriving from the distant lands of Scythia, denied refuge in Ireland, and sailing to Scotland, where they carved out a kingdom. However, archaeological evidence and early Roman texts suggest they were more likely the descendants of native Iron Age tribes — such as the Caledonii and the Vacomagi — groups who evolved into what we now recognize as the Pictish people's origin, unified by culture and resistance.

2. What Did the Picts Look Like in Daily Life?

Despite old legends that portray the Picts as naked, tattooed warriors, archaeological evidence shows a much more refined and well-dressed society. Key features of their appearance include:

Clothing and Personal Adornment

Woolen tunics and cloaks, often fastened with decorative bronze or silver brooches.

Use of bone or antler combs for grooming suggests they cared about hair and appearance.

Patterned textiles shown on carvings, possibly early forms of Pictish weaving.

Hairstyles and Grooming

Stone engravings depict curled hair, styled beards, and tied-back hairstyles.

Clean, maintained grooming tools found in burials imply everyday self-care.

Status and Accessories

Riders and warriors are depicted wearing belts, fitted garments, and sometimes weaponry, indicating social rank.

Jewelry such as pins, bracelets, and finely crafted items reveals a culture that valued craftsmanship.

What Science Reveals? A facial reconstruction from Rosemarkie shows a real Pictish man with strong features and a distinctive look, offering a rare glimpse into the people behind the stones.

In reality, the Picts were well-groomed, well-dressed, and expressive in their clothing and appearance — far from the primitive image often suggested by myth.

3. Pictland: The Homeland of the Scottish Picts

Before diving into borders and kingdoms, imagine journeying through early medieval Scotland: mist rolling off pine-covered hills, stone fortresses perched on cliffs, and carved standing stones rising from the earth. This was Pictland — a landscape steeped in mystery.

Geography and Territory of Ancient Pictland

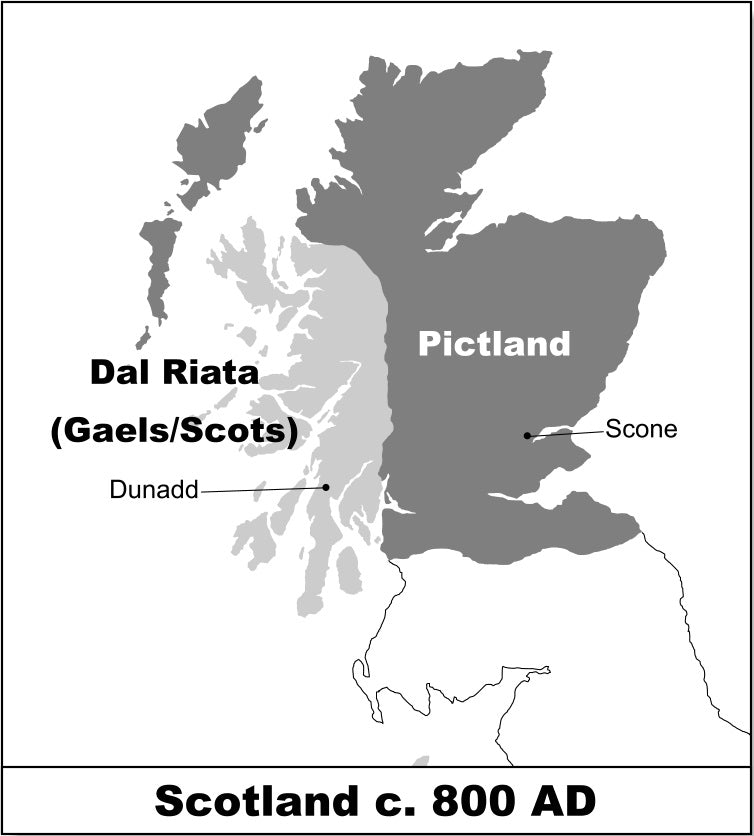

“Pictland,” as modern historians call it, stretched across northern and eastern Scotland. From the rocky coasts of Caithness to the rich farmlands of Moray and the Tay Valley, the Picts held a vast and often fluid territory.

Their influence extended to the Orkney and Shetland Islands, though the western edges of their land were frequently contested with Gaelic-speaking Scots.

The Rise of the Kingdom of Fortriu

Pictland was not a single unified state but a collection of regional kingdoms, including Circinn (Angus and the Mearns), Fib (Fife), Cat (Caithness and Sutherland), Ce (Aberdeenshire), Fotla (Atholl), and Ross in the north. Each kingdom had its own leaders, local power bases, and shifting alliances.

Among them, Fortriu — likely centred around the Moray Firth and Inverness area — emerged as the most powerful. Its strategic location, fertile land, and strong hillfort centres such as Craig Phadrig gave it both military and political advantages over neighbouring kingdoms.

By the 7th century, kings like Bridei mac Beli led Fortriu to dominate the Pictish world. Through successful campaigns, diplomacy, and control over important religious communities, Fortriu gradually unified many Pictish groups under its leadership. This unification gave the Picts a stronger, more coordinated identity — one capable of resisting external threats from Northumbria and shaping the future of early Scotland.

4. Pictish Society and Culture: How the Scottish Picts Lived

Much of what we know about the Picts comes not from written records but from the ground beneath our feet. Archaeological discoveries reveal a society far more organized and sophisticated than early historians once assumed.

Pictish Clans and Matrilineal Kingship

Ever wondered what life was like behind the carved stones? Let’s step into a Pictish village…

Pictish society was clan-based, and intriguingly, royal succession often followed the female line. This matrilineal practice set them apart from neighboring cultures and may have given women a unique social role in their politics and lineage traditions.

Agriculture, Trade, and Elite Lifestyle

Far from being wild barbarians, the Picts were sophisticated agriculturalists and skilled traders. They cultivated barley and oats, raised livestock, and hunted deer and boar with dogs. Archaeological finds from Rhynie and Tap o’ Noth show evidence of wine imported from the Mediterranean and French glassware — proof of elite Pictish households with far-reaching connections.

Burial Traditions and Archaeological Discoveries

Pictish burial practices offer valuable insight into their beliefs and social structures. Unlike the towering symbol stones, their cemeteries were more subtle — yet just as telling.

Recent excavations at Tarradale in the Highlands revealed an extensive burial site featuring at least 18 round and 8 square barrows — mound graves that have mostly eroded but are still visible through crop marks. These structures hint at a hierarchical society that marked elite burials in unique ways.

Other barrow cemeteries, such as those at Garbeg and Whitebridge in Inverness-shire, remain partially intact and visitable today. The variation in burial types — from square to round — may indicate differing tribal customs, regional identities, or social status.

5. Pictish Symbols and Art: Decoding the Mysterious Stones

Pictish artistry is unlike anything else in Europe. At the heart of it are their symbol stones with Pictish patterns — slabs carved with mysterious icons like crescents, V-rods, beasts, and combs. Scholars believe these were personal name markers or clan identifiers. Some Pictish patterns are deeply abstract, others depict animals or tools, but none are fully deciphered.

Symbol Stones and Their Meanings

Found across northern Scotland, these stones are a treasure map of the Pictish world. The Aberlemno Stone in Angus, the Sueno’s Stone in Moray, and the Shandwick Stone in Easter Ross are prime examples. One slab may show warriors on horseback; another, a mirror-and-comb symbol—perhaps signifying status or vanity. These designs evolved over centuries, merging with Christian symbols in the later period.

Cave Carvings and Pictish Symbols at Jonathan’s Cave

Another fascinating example of Pictish art can be found in Jonathan’s Cave, located at East Wemyss in Fife. Unlike traditional standing stones, this seaside cave features Pictish symbols carved directly into the sandstone walls — including the crescent and V-rod.

These rare carvings offer a glimpse into how Picts expressed their identity even in secluded or sacred spaces, proving their symbols weren’t limited to monuments alone.

Pictish Jewelry, Metalwork, and Artistic Style

Beyond stones, the Picts crafted intricate silver brooches, pins, Pictish embroidery designs, and animal figurines. The craftsmanship rivaled their Irish and Anglo-Saxon neighbors. Sites like Rhynie unearthed fragments of fine metalworking, showcasing the Picts' eye for luxury and detail.

6. Pictish Warriors and Battles: How the Picts Defended Ancient Scotland

For centuries, the Picts found themselves at the center of conflict — against Romans, Northumbrians, and rival kingdoms. These battles did more than defend their borders; they shaped the identity and destiny of early Scotland.

The Picts and Their Conflict With the Romans

The Battle of Dun Nechtain and Its Significance

In 685 AD, the Battle of Dun Nechtain marked a turning point. Under King Bridei III, the Picts crushed the powerful Northumbrians. This battle solidified Pictish independence and was key in establishing Scotland’s future borders. It was more than a military win—a declaration of identity.

7. The Christianization of Pictland: Religion and Transformation

Before Christianity reshaped Pictland, the Picts followed deeply rooted local traditions. But what happens when a powerful new faith enters an already rich spiritual landscape?

The arrival of Christianity marked one of the most significant turning points in Pictish history. More than a spiritual shift, it altered politics, diplomacy, art, and the Picts’ place within the broader early medieval world.

Saint Columba and the Conversion

In the late 6th century, Christianity swept through Pictland, largely thanks to the Irish missionary St. Columba. He met with King Bridei and established the monastery at Iona. This spiritual powerhouse connected the Picts to Christian Europe. Earlier efforts by St. Ninian had also begun the process in the south.

The Impact on Culture and Art

Christianity didn’t erase Pictish culture — it transformed it. Cross slabs began to incorporate traditional symbols alongside Christian crosses. Burial mounds became more aligned with Christian rites, and literacy spread through monasteries. Art flourished, blending ancient motifs with spiritual symbolism.

8. The Decline of the Picts: What Happened to the Pictish Tribes?

The Picts are often said to have vanished — but did they really? Their decline was less a disappearance and more an evolution under the weight of invasion, internal strife, and shifting identities.

Viking Invasions and Internal Conflict

By the 9th century, the Viking Age had arrived. Raids devastated monasteries, such as Portmahomack, where once-priceless Pictish carvings were smashed. Coupled with dynastic infighting, Pictish power began to erode. The assassination of Áed, the last known king of the Picts in 878, marked a symbolic end.

The Rise of Alba and Gaelicization

Kenneth MacAlpin, a ruler of Pictish and Gaelic descent, unified Pictland with the Gaelic Dál Riata, creating the Kingdom of Alba.

Over time, the Pictish language faded and was replaced by Gaelic. The Irish church’s influence reshaped spiritual life, and the term “Pict” disappeared from chronicles altogether. But the people remained — they evolved.

9. The Legacy of the Scottish Picts in Modern Scotland

What remains of the Pictish people today? More than you might think. From genetic studies to enduring place names and iconic symbol stones, the Pictish spirit survives in surprising ways across Scotland.

Genetic Traces and Cultural Echoes

Sites You Can Visit Today

Remembering the Pictish Spirit

The Scottish Picts weren’t just warriors with painted bodies — they were builders of kingdoms, makers of art, and shapers of early Scotland. Though they vanished from the written record, their story didn’t end. It lives on in stone, soil, and blood. When you next wander through Scotland’s misty highlands or stand before a symbol stone etched in mystery, you’re not just looking at history — you’re staring into the soul of a people who helped shape a nation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are the Picts and Scots the same?

No, the Picts and Scots were distinct groups. The Picts were native to eastern and northern Scotland, while the Scots originated from Ireland. They later merged to form the Kingdom of Alba.

What did the Scottish Picts look like?

The Scottish Picts likely had fair or reddish hair, light skin, and wore decorated cloaks and brooches. Facial reconstructions support this Celtic appearance.

Do Scots have Pictish DNA?

DNA study reveals the origins of the medieval Picts ...The analysis showed that Picts descended from local Iron Age populations, who lived across Britain before the arrival of mainland Europeans. Additionally, the researchers found genetic similarities between the Picts and present-day people living in western Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, and Northumbria.

Where did the Picts come from originally?

The Picts originated from native Iron Age tribes in northern Scotland, such as the Caledonii. They evolved locally, not through migration from distant lands.